Layman’s definition of tax avoidance is reducing a tax payer’s liability without breaking the law. This is the most likely definition availed by search engines over the internet, you can try. Thus tax avoidance sounds legal, in fact the right thing to encourage taxpayers to do. Proponents of this argument quickly contrast tax avoidance with tax evasion by pointing out tax evasion is illegal while tax avoidance is not. Whereas it’s obvious that tax evasion is illegal, we need to be a little careful before we define tax avoidance as legal. For starters the words evasion and avoidance are not perfect opposites or antonyms. Outside taxation cycles these words are used interchangeably in other words they are synonyms. Borrowing from French, tax avoidance is évasion fiscale closely translated to mean Fiscal evasion while tax evasion is fraude fiscale or otherwise fiscal fraud. Looks like tax avoidance and tax evasion are closely related.

Tax laws across the globe extend deductions, exemption of certain incomes and special tax incentives which essentially reduce the revenue of the state to the benefit of the tax payer. These concessions are for the mutual benefit of the state and the payer for some specific reasons thus tax payers are encouraged to apply them. It is obvious for a tax payer to arrange his financial affairs in a manner that reduces the tax obligations because the law so permits. Organizing the financial conduct of a person in the most tax efficient way is known as tax planning which is lawful. Tax planning involves careful analysis of the financial affairs of a person and ensuring that all transactions are undertaken in full compliance of the tax law. That implies paying what ought to be paid and claiming what ought to be claimed. Tax planning or tax sheltering introduces controversy in revenue administration and compliance. Whereas tax payers are encouraged to apply the law for their benefit, they may twist it and end creating revenue leakages. If taxpayers are allowed to organize their financial affairs to minimize their fiscal obligations, then they can carefully devise transactions for the purpose of beating the law. Bearing in mind that the onus of declaring income for tax purposes rests with the tax payer, a transaction might be altered to fit what is within the law with the intention of reducing tax bill. How will the tax gatherers deny that the transaction did not occur while in reality it did? How will they say it’s illegal where the law is clear? Quick example According to paragraph 53 of the first schedule of the income tax act (ITA CAP 470), bonus and overtime pay to low income employees ( employees earning Kshs. 12,298 per month or less before the bonus or overtime) is exempted from tax in Kenya. The spirit behind this provision is to avoid overtaxing poor employees out of their extra sweat. Now suppose an employee earning Shs 50,000 enters in to an arrangement with the employer to have a contractual salary of Shs. 10,000 (less than Shs.12,298) with a bonus paid in the range of Shs.35,000 to 45,000 conveniently fluctuated within this range to make it look like a real bonus. This scenario would likely create an argument of whether it’s logical to pay a bonus more than the basic pay and so on. But you see the law exempts bonus payable to low income employees and does not envisage this craftiness.

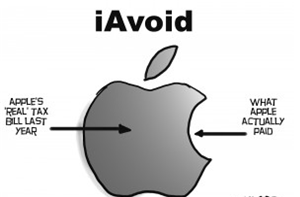

The doctrine of substance over form The above scenario presents a classic example of trying to bend the law hoping not to break it. This exactly what Tax avoidance is and that makes it the greatest headache to tax gatherers. This is complicated by the fact that the written rules might not be violated but manipulated to create massive revenue leakages. The common way of avoiding tax is through transfer pricing practiced by multinational giants. Google, apple, Starbucks Amazon Vodafone and other fortune 500 companies are on record for paying very low amounts of tax due to profit shifting to tax havens. For instance Facebook paid £15.8m in tax in the UK in 2018 despite collecting a record £1.3bn in British sales which is less than 1% of the sales value. Their profits increased by 6% while their sales had increased by 50%. (Click Here to Read full story)

Tax avoiders keep mutating their tricks and wits, thus the law makers are ever catching up in sealing loopholes and creating anti-tax avoidance provisions. Bear in mind tax avoidance cuts across many jurisdictions where different laws apply. There is general tendency to apply the doctrine of substance over form which comes in handy in defeating this cunning practices. Substance over form read in full means “the economic substance or reality of a transaction prevails over its legal form”. This concept which is also a general principle in accounting is applied by considering the economic sense of a transaction and not its mere legal interpretation. In taxation the Doctrine allows the tax authorities to ignore the legal form of an arrangement and to look to its actual substance in order to prevent artificial structures form being used for tax avoidance purposes. Origin of the doctrine – Gregory v. Helvering case (Click Here to read case in full) Evelyn Gregory was the owner of all the shares of a company called United Mortgage Company (“United”). United Mortgage in turn owned 1,000 shares of stock of a company called Monitor Securities Corporation (“Monitor”). On September 18, 1928, she created Averill Corp and, three days after, transferred the 1000 shares in Monitor to Averill. On September 24, she dissolved Averill and distributed the 1000 shares in Monitor to herself, and on the same day sold the shares for $133,333.33. She claimed there was a cost of $57,325.45, and she should be taxed on a capital net gain on $76,007.88. On her 1928 federal income tax return, Gregory treated the transaction as a tax free corporate reorganization, under the Revenue Act of 1928 section 112. The Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Guy T. Helvering, argued in economic substance there was no business reorganization, that Gregory owned all three corporations and was simply following a legal form to make it appear like a reorganization so she could dispose of the Monitor shares without paying substantial income tax. Accordingly, she understated her liability by $10,000. The presiding jury made this statement in his ruling “In these circumstances, the facts speak for themselves and are susceptible of but one interpretation. The whole undertaking, though conducted according to the terms of [the statute], was in fact an elaborate and devious form of conveyance masquerading as a corporate reorganization, and nothing else” The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. Legal form of the above case was that a capital gain was realized which attracted lesser taxes as per their laws, the economic reality was that a gain was made overnight which in all sense was a dividend except by its legal definition. The legal definition did not matter. Anti-tax avoidance provisions in Kenya

Kenya like many other countries has in its tax laws the general anti-tax avoidance rule (GAAR) and specific anti avoidance rules (SAARs). GAARs have the advantage of flexibility and give tax authorities an instrument which allows them to react fast to any new perceived tax avoidance scheme by disregarding arrangements that have been put in place mainly to obtain a tax benefit. However, as their critics rightly invoke, GAARs also confer great power and responsibility upon the tax adjudicators. SAARs on the other hand are often more predictable in their application, and therefore provide more legal certainty, they are also easier to circumvent by taxpayers. When a new arrangement is designed by a taxpayer that is not yet in the scope of a SAAR, the taxpayer can benefit from this arrangement for a certain period of time until it is clamped down by a new SAAR adopted by the lawmakers. ( Click Here to Read more on GAARs and SAARs) Kenya’s General anti -tax avoidance rule (GAAR) is found in Section 23 of the income tax act cap 470 (sec 23) This rule empowers the commissioner to collect taxes avoided if he is of the opinion that a certain transaction has been initiated with the very intention of reducing tax payer’s tax liability. By invoking this rule, the commissioner is empowered to reverse the effects of a dubious transaction by making appropriate adjustments and collecting the taxes thereof. Besides this general provision the income tax act has the following specific tax anti-avoidance provisions (SAARs)

- Sec 24- tax avoidance by non-distribution of dividends. Dividend income is subject to withholding tax while capitals gains realized on shares are as of this day not taxable. This fact makes it convenient for a company not to pay dividend so as to deny the exchequer the applicable tax. Read the section and see enormous powers granted to the commissioner to collect the tax.

- Sec 16(j) – This are popularly referred to as thin capitalization rules- A firm is thinly capitalized if it is foreign controlled and its debt component is three times or move the value of equity. Essence of the rule is to limit deductible interest which would otherwise be abused.

- Sec 15 (e) 7 – The famous doctrine of specified sources of income. This section disallows offsetting losses from one activity against gains from a different activity. Without this rule, most of the tax payer in this county engaging in unproductive ventures will bring in humongous losses from activities to their tax bill and as a result create a tax refund position.

- Deemed interest- This applies to foreign companies advancing interest free loans to resident companies. The motivation for having no interest on such loans is to deny the government the withholding tax that would have been charged on the interest payable to a non-resident. The law empowers the commissioner to deem an interest and demand the withholding tax.

- Transfer pricing rules- Multinationals abuse their group structure and price transactions between their subsidiaries conveniently to reduce the tax burdens. This involves careful study of the different tax regimes and making sure they report as little profits as possible in unfavorable tax jurisdictions and in most cases shift all the profits to low tax regimes or tax havens for that matter. Transfer pricing coupled with the emergence of digital economies poses a big threat to emerging economies, Kenya being one of them. Kenya has the transfer pricing rules of course borrowed from the Organization for economic cooperation development (OECD) which specify how international transactions should be priced.

In summary and to answer our question is tax avoidance legal? the heaviest penalty in Kenyan tax is actually on tax avoidance. The tax procedures act 2015 (TPA sec 85) imposes 200% penalty on tax avoidance.